Adrian Piper

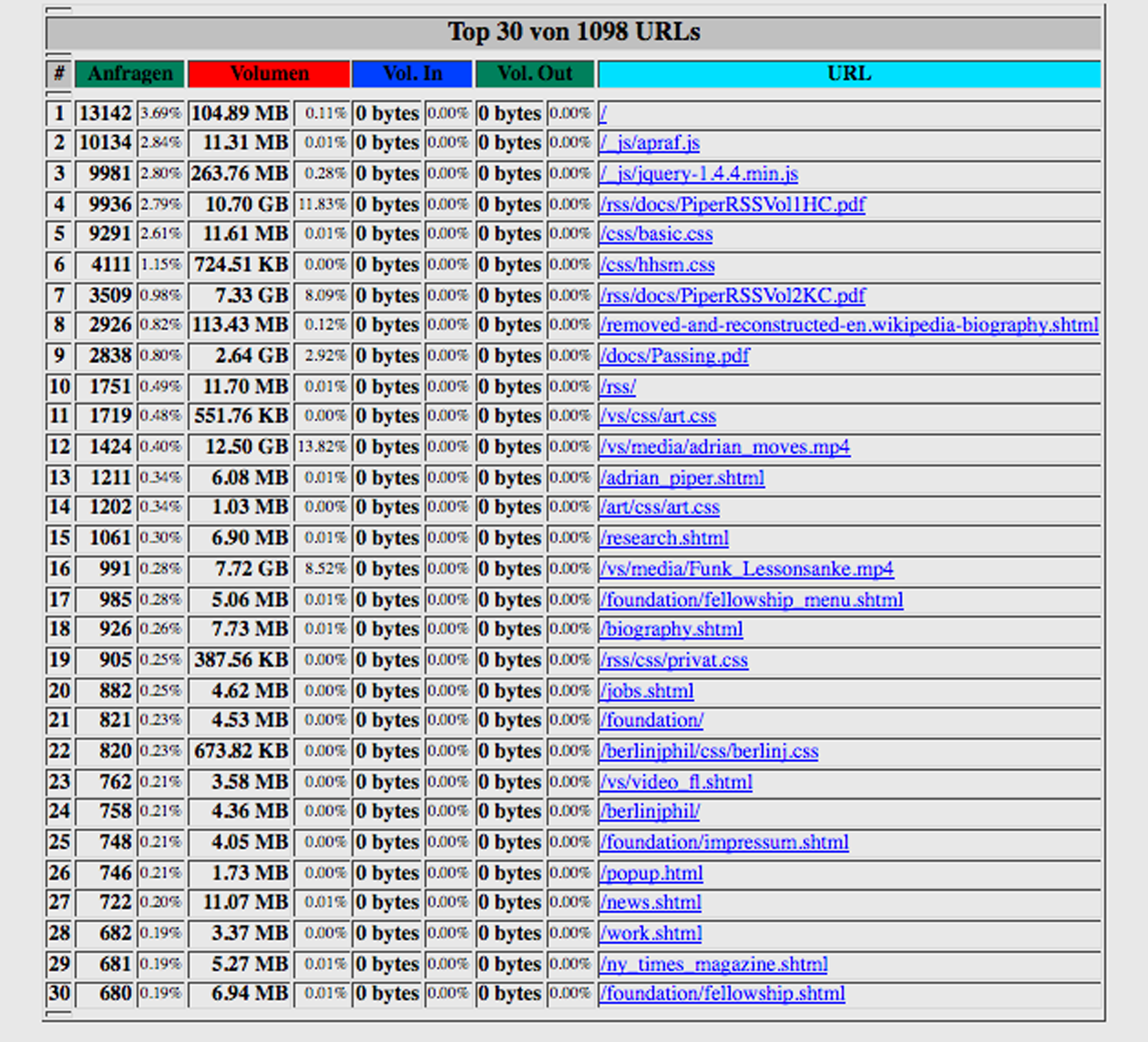

Removed from en.Wikipedia, the free “encyclopedia,“ reconstructed here at Adrian Piper’s request in September 2013, and updated at least once a year (most recently in March 2024). The en.Wikipedia article falsely claimed to offer biographical information about Adrian Piper, when in fact it had been replaced, post-publication, with its editors’ marginal comments, criticisms and to-do lists. As this practice is substandard with respect both to the traditional purpose of an encyclopedia and to academically acceptable editorial standards, Adrian Piper repeatedly requested deletion of the article. Three Wikipedia members refused to post these observations at the relevant discussion page. In December 2013, the article was again replaced by a new one, which apparently had not been fact-checked and contained racist stereotypes and numerous factual errors.

Adrian Margaret Smith Piper (born September 20, 1948) is a first-generation Conceptual artist and analytic philosopher who was born in New York City. Since 2005 she has lived and worked in Berlin, where she runs the Adrian Piper Foundations.

Contents

| Born | 1948 New York, NY, USA |

| Fields | Conceptual Art, Analytic Philosophy |

| Education | New Lincoln School School of Visual Arts City College of New York University of Heidelberg Harvard University |

| Website | http://www.adrianpiper.com |

Personal and "Racial" Background

Piper publicly identifies as an American woman of acknowledged African ancestry. She rejects the adjectives “Black” and “White” as racist stereotypes . Like all Americans, she is "racially" (that is, ethnically) mixed. Piper is 1/32 Malagasy (Madagascar), 1/32 African of unknown origin, 1/16 Igbo (Nigeria), and 1/8 East Indian (Chittagong, East Bengal, India [now Bangladesh]). She has predominantly British and German family ancestry. Detailed genealogies for all four of her grandparents are available at the Adrian Piper Foundations Genealogies website page. She is a direct descendant of Reverend John Rogers, first Protestant martyr of the Anglican revolution, burned at the stake in 1555. Educating the general public about the pervasiveness of miscegenation and the fictitiousness of the concept of race has been a recurring theme in her work, beginning with her first high school biology term paper in genetics in 1962 and including the public announcement of her retirement from being “black” in 2012. Piper grew up in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan. Her father, Daniel Robert Piper, was a lawyer and nephew of William T. Piper, the aviator and founder of the Piper Aircraft Company. Her mother, Olive Xavier Smith Piper, was the English Department administrator of the Open Admissions Program at the City College of New York and the only daughter of Reginald Audley Smith, a planter and accountant, and Margaret Ann Norris Smith, a high school teacher. Piper left New York City in 1974 and later lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts; West Berlin, Germany; Heidelberg, Germany; Ann Arbor, Michigan; Menlo Park, California; Washington, D.C.; La Jolla, California; Wellesley, Massachusetts; Los Angeles, California; and Cape Cod, Massachusetts, before settling in Berlin, Germany in 2005. Her bi-lingual autobiographical book, Escape to Berlin: A Travel Memoir/Flucht nach Berlin: Eine Reiseerinnerung appeared in 2018 as the first print publication of the APRA Foundation Berlin.

Education and Academic Career

Piper attended Riverside Church nursery and kindergarten. She entered the New Lincoln School grammar school in first grade, and graduated from its high school in 1966. During high school she also attended the Art Students’ League. She began exhibiting her artwork internationally at the age of twenty, and graduated from the School of Visual Arts in 1969 with an A.A. in Fine Art and a concentration in painting and sculpture. While continuing to produce and exhibit her artwork, Piper received a B.A. Summa Cum Laude with Research Honors in Philosophy and a minor in Medieval and Renaissance Musicology from the City College of New York in 1974. For graduate school in philosophy she attended Harvard University, where she received an M.A. in 1977 and a Ph.D. in 1981 under the supervision of John Rawls. She also studied Kant and Hegel with Dieter Henrich at the University of Heidelberg in 1977-1978. Piper taught philosophy at Georgetown, Harvard, Michigan, Stanford, and UCSD. In 1987 at Georgetown University, Piper became the first tenured African American woman professor in the field of philosophy. In 2008, for her refusal to return to the United States while listed as a “Suspicious Traveler” on the U.S. Transportation Security Administration Watch List, Wellesley College forcibly terminated her tenured full professorship while she was on unpaid leave in Berlin. In 2011 the American Philosophical Association awarded her the title of Professor Emeritus.

Contributions in Philosophy

Adrian Piper’s principal philosophical publications are in metaethics, Kant, and the history of ethics. Her two-volume study in Kantian metaethics, Rationality and the Structure of the Self, Volume I: The Humean Conception and Rationality and the Structure of the Self, Volume II: A Kantian Conception, was accepted for publication by Cambridge University Press in 2008 and since then has been available at the APRA Foundation website as two open access e-books (second edition 2013). This study critically surveys the major moral theories of the late 20th century, develops a Kantian metaethical theory anchored in Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, and integrates standard decision theory into classical predicate logic. It has been praised by anonymous peer reviewers as “groundbreaking,” “very powerful,” “original and important,” “brilliant,” “indispensable,” “a blockbuster,” and “a highly significant contribution.”[1]

Do we at least have the capacity ever to do anything beyond what is comfortable, convenient, profitable, or gratifying?

Can our conscious explanations for what we do ever be anything more than opportunistic ex post facto rationalizations for satisfying these familiar egocentric desires?

If so, are we capable of distinguishing in ourselves those moments when we are in fact heeding the requirements of rationality, from those when we are merely rationalizing the temptations of opportunity?

I am cautiously optimistic about the existence of a buoyant device – namely reason itself – that offers encouraging answers to all three questions. Without hard-wired, principled rational dispositions – to consistency, coherence, impartiality, impersonality, intellectual discrimination, foresight, deliberation, self-reflection, and self-control – that enable us to transcend the overwhelming attractions of comfort, convenience, profit, gratification – and self-deception, we would be incapable of acting even on these lesser motives. Or so I argue in this project.”

-- Opening passage from Rationality and the Structure of the Self, Chapter I. General Introduction to the Project: The Enterprise of Socratic Metaethics

Rationality and the Structure of the Self was the culmination of 34 years of work, parts of which were previously published in article form. One early article, “Two Conceptions of the Self” (1985)[2] introduced Piper’s distinction between the Humean and the Kantian conceptions of the self, motivation and rationality. In Rationality and the Structure of the Self, she argues that the second half of the 20th century saw the development in Anglo-American analytic philosophy of a battle for supremacy between these two competing conceptions in ethics. Piper defines the Humean conception as consisting in the belief-desire model of motivation plus the utility-maximizing model of rationality; and the Kantian conception as modeling both motivation and rationality on the canons of deductive and inductive logic. The Kantian conception of the self thereby accords priority to freedom, autonomy and moral obligation over the satisfaction of desire and the maximization of utility. Piper claims that in this competition, both combatants have been handicapped by their own assumptions. In Rationality and the Structure of the Self she surveyed this historical development and proposes solutions to several of the still-unresolved problems it engendered.

Piper examined the Humean conception of the self in depth in Volume I: The Humean Conception. There she acknowledges the impressive historical pedigree of this conception in Hobbes, Hume, Bentham, Mill, and Sidgwick; and analyzes the foundations it provides to contemporary utilitarianism, virtue theory and social contract theory in philosophy.[3] Piper also traces the influence of the Humean conception in economics, psychology, and political theory because of its technical formalization in decision theory and neoclassical economics by Ramsey, Savage, von Neumann & Morgenstern, Allais, and others.[4] She argues that its wide sphere of influence in the social sciences has led late-20th century moral philosophers to presuppose the Humean conception as a given in constructing foundations for their normative moral theories.[5] However, she contends, close analysis of both the belief-desire model of motivation and also the utility-maximizing model of rationality, in both informal and axiomatized versions, reveals that all such formulations are not only either vacuous or internally inconsistent. They also conceal intensional presuppositions that make it impossible to state in what, exactly, the irrationality of a cycle ordering consists; and therefore rob decision theory’s technical apparatus of a viable and formally valid consistency criterion.[6]

-- Excerpt from Rationality and the Structure of the Self, Volume I: The Humean Conception, Chapter II. The Belief-Desire Model of Motivation

Piper criticizes Humean moral philosophers for having displaced these problems onto a straw man: the consequentialist/deontologist debate, rather than confronting them head-on.[7] Consequently, she argues, Humean moral philosophers as varied as Rawls, Nagel, Brandt, Gewirth, Baier, Williams, Frankfurt, Gibbard, Lewis, Goldman, Anderson, Anscombe and others have misguidedly appropriated the Humean conception of the self for foundational purposes.[8] And they have been unsuccessful in their attempts to solve the three insoluble metaethical problems that the Humean conception engenders: of moral motivation, rational final ends, and moral justification.[9] Volume I of Rationality and the Structure of the Self concludes that the Humean conception of the self can be rescued only by embedding it as a special case in a more comprehensive Kantian conception that it implicitly presupposes.[10]

However, Piper also views many Kantian moral philosophers as having also tied their own hands in attempting to formulate an alternative to the Humean conception, by restricting their attention to Kant’s moral philosophy alone. In two earlier articles on Kant-exegesis, “Kant on the Objectivity of the Moral Law” (1994)[11] and “Kant’s Intelligible Standpoint on Action” (2000)[12], she contended that Kant’s own moral theory cannot be properly interpreted without reference to the historically prior Critique of Pure Reason, in which all of the significant technical terms that inform the Groundwork and second Critique are introduced. She suggests that ignoring Kant’s first Critique makes it impossible for contemporary Kantian moral theory to outcompete the Humean conception’s highly refined and systematized formalization of action theory, which proves its success through practical application in the social sciences.[13]

-- Excerpt from Rationality and the Structure of the Self, Volume II: A Kantian Conception, Chapter V. How Reason Causes Action

With Rationality and the Structure of the Self, Volume II: A Kantian Conception, Piper aimed to remedy these oversights. She finds in Kant’s first Critique inspiration for proposed alternative models of motivation, rationality, and the self that are constructed on the relatively firm foundation of classical predicate logic – the same foundation on which Kant’s own conception of reason relied.[14] She proposes a way to integrate standard decision-theoretic axiomatizations into this foundation without loss of predictive power, by (1) rendering explicitly the intensionality of preference orderings using classical predicate logic; and (2) extending the Boolean connectives and quantificational notation of that logic to subsentential constituents.[15] In addition, she argues that integrating the Humean belief-desire model of motivation into a Kantian model of reason as motivation implies solutions to the problems of moral motivation, rational final ends, and moral justification that the Humean conception engendered.

In this second volume, Piper develops a conception of human agency, based on a foundation of logical consistency as literal self-preservation. She proposes two criteria of consistency for the set of concepts that rationally structure the self in the ideal case: horizontal consistency of cognitively operative concepts with one another, which applies the quantified law of non-contradiction to subsentential constituents; and vertical consistency of lower-order concepts with higher-order ones, which applies the quantified law of modus ponens to the inferential relationship among such constituents. Final ends that satisfy these two criteria are rational; substantive moral theories that satisfy them are rationally justified; and actions that are guided by them include those which are morally motivated. [16]

Piper argues that human beings are naturally disposed to preserve at least the appearance of such consistency, both in their cognitions and in their actions, even when the practical reality falls short. This practical shortcoming she refers to as pseudorationality. She argues that this overriding disposition explains how reason can be motivationally effective in the absence of desire, and why it so rarely is in practice.[17] Piper applies this conception of the self and agency, first, to both analyze and also justify the practice of whistle blowing[18]; and second, to an analysis of xenophobia that implies both its inevitability and also its susceptibility to rational reform.[19] In an early article, “Moral Theory and Moral Alienation” (1987), Piper concluded that the phenomenon of moral alienation that has received so much attention in the metaethical literature is a natural by-product of possessing and exercising our cognitive and rational capacities.[20] She concludes Volume II of Rationality and the Structure of the Self with the further argument that without so-called moral alienation, we would be unable to grasp meaning, forge relationships with others, or act transpersonally in the service of selfless or disinterested moral principles.[21] Since online publication of the first edition in 2008, this two-volume work has consistently received more hits at the APRA website than any other pages. In October 2018, the online discussion forum Critique presented an author-meets-critics symposium on Rationality and the Structure of the Self, with comments by Professors Paul Guyer (Brown University) and Richard Bradley (London School of Economics) and a reply by Piper.

The Berlin Journal of Philosophy

Piper founded The Berlin Journal of Philosophy in 2011. The Journal was an English-language blind-submission, double-blind, peer-reviewed, open-access journal that aimed to publish articles on all topics in the four traditional major areas of philosophical specialization, namely epistemology & metaphysics, logic, value theory, the history of philosophy, and their established subspecialties.[22] It innovated in adhering strictly to simultaneous policies of blind submissions, double-blind review, and anti-plagiarism.[23] The Journal was copyrighted, administered and published by the APRA Foundation Berlin, an independent research organization unaffiliated with any department, institute, school, college, university, or other academic institution.

Piper founded the Journal while seeking to solve the problem of how to reconcile the conflicting requirements of anti-plagiarism and blind submissions in academic publishing. For those authors who aspire to peer-reviewed publications accepted exclusively on the basis of their quality, or at least to avoid treatment affected by knowledge of the author’s identity, a policy of blind submissions is a necessary supplement to double-blind reviewing: By concealing the author’s identity even from administrators, it guards against information slippage, whether intentional or unintentional, between administrators and referees. For those authors whose publications receive rather more use than mention by their colleagues, a strong and consistent anti-plagiarism policy, of the sort recommended by the Office of Research Integrity,[24] the Committee on Publication Ethics,[25] or the Singapore Statement on Research Integrity[26] is equally important. These two procedures appear to be mutually incompatible: A robust blind submissions policy requires that the author’s identity not be disclosed, even to administrators, until after referees have made a positive decision on the paper; and, if a negative one, not at all. A robust anti-plagiarism policy requires that plagiarism sanctions apply independently of whether or not the paper is accepted for publication; and this, in turn, requires the author’s identity to be known at least to administrators in advance of that decision. [27] Whereas blind submission prohibits author disclosure until after the publication decision, anti-plagiarism necessitates author disclosure before the publication decision. It would seem to be impossible to satisfy the requirements of both simultaneously.

In collaboration with the APRA Foundation Berlin web master, Piper developed a fully computerized procedure for submitting scholarly papers for publication in academic journals that reconciled these two desiderata. The procedure, a simple web application template, satisfied the requirements of blind submission and double-blind review, and was also compatible with a robust anti-plagiarism policy. On 7 April 2011, she publicly announced this application and offered it to any journal that might wish to consider it. No journal or individual expressed interest in this offer. But in the process of researching the mechanics of the procedure, she was “compelled to conjure in imagination the philosophy journal in which such a procedure could most easily be put to use, and concluded that [she] would have to establish it [her]self.”[28] The result was The Berlin Journal of Philosophy, an innovative experiment that offered a different way of implementing the traditional values of academic research publications.

The Journal was also unusual in several other respects. It was slated to appear whenever a paper that met the requisite quality criteria had been selected. It explicitly solicited specialized paper submissions in all areas of academic philosophy – including the history of non-Western as well as Western philosophy.[29] It rejected the conventional conception of refereeing as an unpaid service to the field that all academics are professionally obligated to render when called. Instead, it required referees to apply voluntarily for the job and make a contractual commitment, on the reasoning that referees would be more amenable to following rules to which they had voluntarily agreed.[30] It also offered referees a nominal honorarium for each refereed paper that satisfied the terms of the Anonymous Referee Contract, thus explicitly acknowledging the value of their service.[31] The Contract committed referees to specified refereeing practices, including administration of a detailed anti-plagiarism policy. This policy defines the concept of plagiarism not motivationally, but rather behaviorally and gradatim. It was the failure to meet the obligation of bibliographic citation to a source of one’s research itself, not the motive for this failure, which was held to account by the Journal’s anti-plagiarism policy.[32] The Journal’s Anonymous Referee Contract also strictly prohibited referees from disclosing their service as referees for the Journal to anyone, and therefore from listing it on their CVs.[33] This provision effectively protected the referee’s freedom to evaluate a submitted paper solely on its merits, without fear of professional repercussions even in those difficult and painful cases where the paper raised plagiarism issues. The price of this freedom was that the referee had to relinquish the professional advantages of being identified as a referee for the Journal.[34]

The attempt to recruit mathematical logicians to the team of anonymous referees was consistently unsuccessful. As a Call For Papers in all areas of philosophy could not be announced without them, the Journal issued no Calls For Papers, and therefore published no issues. As of 01 January 2020, Piper discontinued it as an active enterprise, with the exception of its annual survey, English-Language Philosophy Journal Paper Submission Policies, which rates the performance of roughly 900 journals in satisfying the requirements of strict blind submission. The Berlin Journal of Philosophy itself satisfied all of these requirements, and continues to offer one possible model for those academic journals whose sole priority is the quality and originality of the papers submitted to them.

Contributions in Art

Adrian Piper’s early LSD Paintings of 1965-67, some of which were executed while she was still in high school, were discovered and curated by Robert del Principe, exhibited for the first time in 2002 at Galeria Emi Fontana in Milan, and quickly entered the international canon of psychedelic art.[35] Influenced by the work of Sol LeWitt in 1967, Piper then embraced the principle of Conceptual art that accords highest priority to the idea or concept that generates a work, and regards different art media – painting, sculpture, drawing, performance, video, installation, soundworks, photo-documentation, etc. – as equally available and valuable instruments for realizing it.[36] Since then, she has maintained this approach to materials in all of her work.[37]

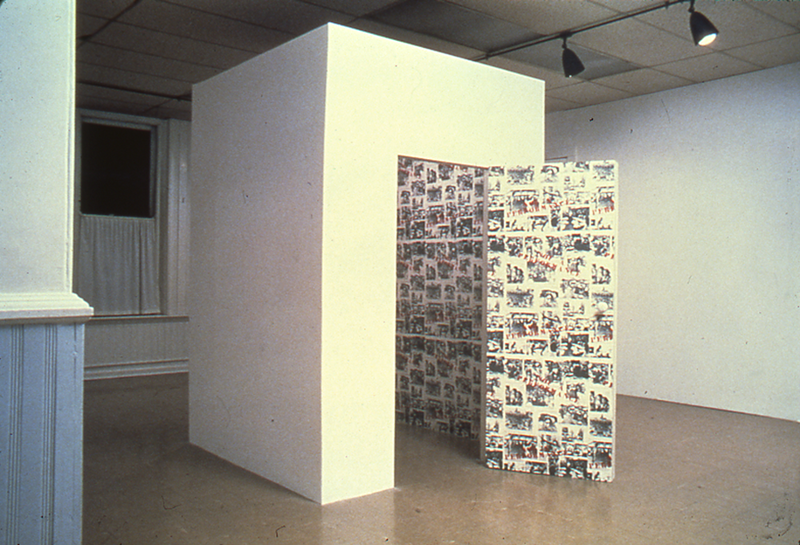

From 1967 to 1970, her early work as a first-generation Conceptual artist brought to bear the techniques and resources of yoga and meditation – what she called the “indexical present,” acquired through her personal practice, on the exploration of consciousness, perception, and infinite permutation using maps, diagrams, photographs and descriptive language.[38] Her Hypothesis: Situation series (1968-1970) forged a connection between passive contemplation of objects and the dynamic character of self-conscious agency navigating through time that then led her briefly into unannounced street performance.[39] In the 1970s, Piper introduced issues of xenophobia, race and gender into the vocabulary of Conceptual art with her Catalysis (1970-72) and Mythic Being (1973-75) performance series.[40] She then introduced explicit political content into Minimalism with her mixed media constructed environment Art for the Art World Surface Pattern (1976).[41]

In the 1980s, Piper sharpened the focus of her artwork, by applying her meditational concept of the indexical present to the interpersonal dynamics of racism and racial stereotyping.[42] Works that explore these themes and strategies include her pencil drawing Self-Portrait Exaggerating My Negroid Features (1981); her collective performance and video Funk Lessons (1982-4); her unannounced Calling Card interactive performances (1986-1990); her mixed media installation Close to Home (1987); her video installation Cornered (1988); and Vanilla Nightmares (1986-1989), her series of racially and sexually transgressive charcoal drawings on pages of the New York Times. Her first retrospective in 1987 at the Alternative Museum in New York, Adrian Piper: Reflections 1967-1987, reintroduced the art public and a new generation of viewers to the media, strategies and preoccupations of first-generation Conceptual art.[43] Her mixed media video installation, The Big Four-Oh (1988), won the New York Dance & Performance Award (the Bessie) for Installation & New Media in 2001.

The 1990s saw Piper extend many of the same concepts and preoccupations to several large-scale, commissioned multi-media works and video installations in the formal tradition of Serial Minimalism. Among these were Vote/Emote (1990),[44] Out of the Corner (1990),[45] What It’s Like, What It Is #1 – 3 (1991-2),[46] and Black Box/ White Box (1992).[47] Piper’s multi-panel photo-text collage series Decide Who You Are (1991-92) combined appropriated photographic imagery with silk-screened drawing and poetically compressed texts, in a sequence of formal permutations on the themes of political disingenuity and self-deception. In 1995, Piper withdrew her work from an important museum exhibition survey of early Conceptual art, in protest against its funding by the Phillip Morris Tobacco Company.[48] To replace it, she created Ashes to Ashes (1995), a photo-text work narrating both of her parents’ deaths from smoking-related diseases.

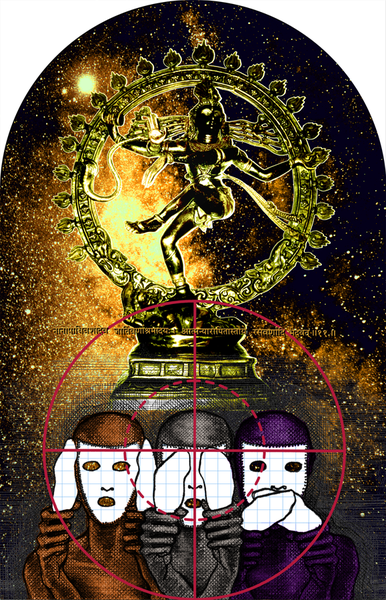

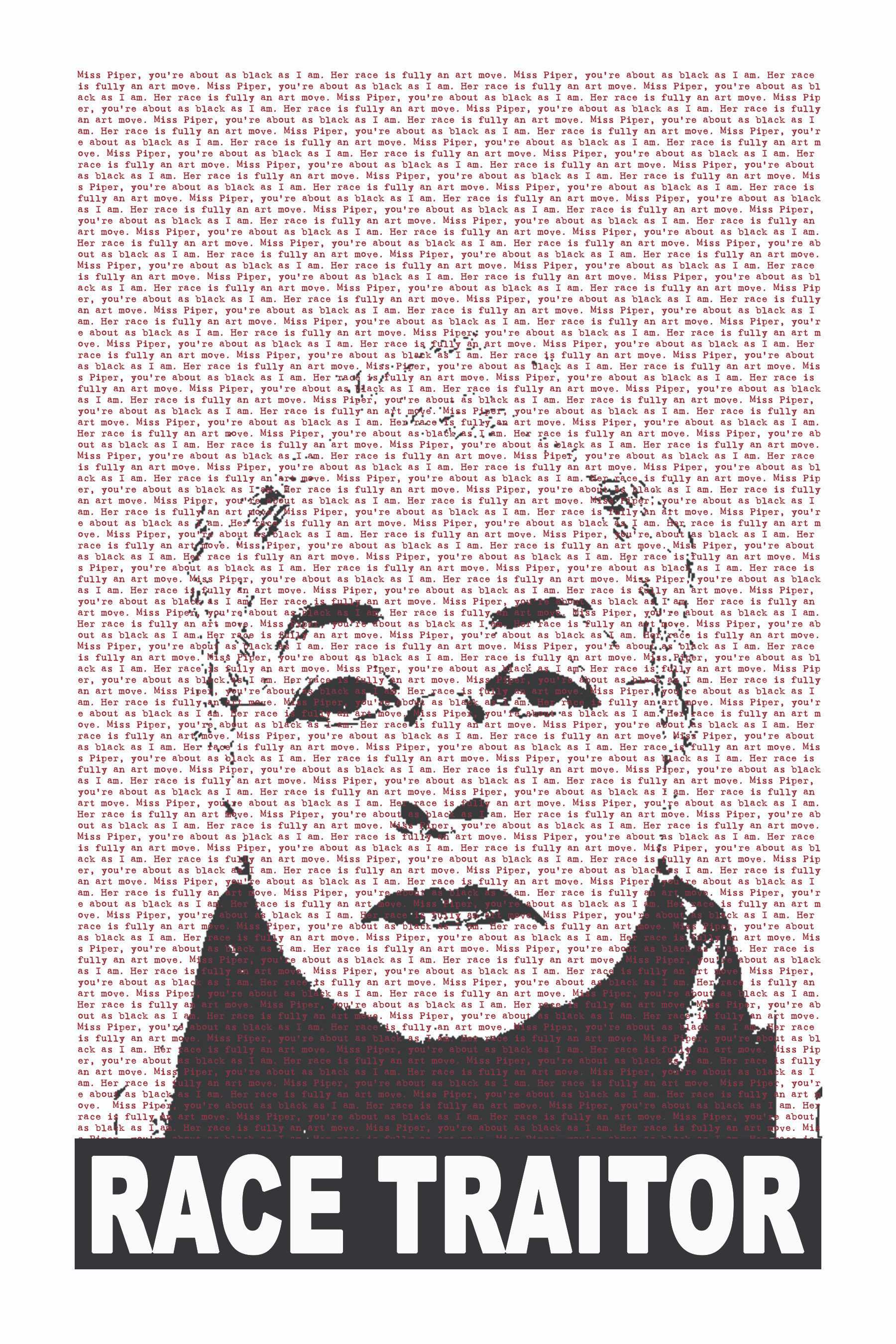

Piper further expanded the vocabulary of Conceptual art to include Vedic philosophical imagery and concepts in 2000, with her silk-screened graphic permutational Color Wheel Series, which combined Sanskrit text with drawing, photography, and representations of a Vedic divinity. Since then she has extended these concepts into an introspective investigation of loss, desire, detachment and self-transcendence in such works as her video YOU/STOP/WATCH (2002) and her open-ended multi-media series Everything (2003- ). Her Vanishing Point series (2009- ) consisting in sculptural installations, drawings and collective performance, further sharpens the focus of her investigation into the nature, structure and boundaries of the ego-self. Race Traitor (2018) satirizes her appearance to those trapped inside those boundaries who strive to fortify them against her.

Adrian Piper’s artwork is in many important collections, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; the Generali Foundation, Vienna; the Aomori Museum of Art, Japan; and the Tate Gallery, London. Her sixth traveling retrospective, Adrian Piper since 1965, closed at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Barcelona in 2004. Her two-volume collection, OUT OF ORDER, OUT OF SIGHT: Selected Writings in Meta-Art and Art Criticism 1967 – 1992 (MIT Press, 1996), is available in paperback. Her seventh traveling retrospective, Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions 1965-2016 opened at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, on 27 March and ran to 22 July 2018. It was the first solo exhibition by a living artist in the museum’s history to occupy its entire sixth floor, and received universal acclaim. Her eighth retrospective, Adrian Piper: RACE TRAITOR, her first European retrospective in over twenty years, opened at PAC Milan in March 2024.

Wahlkampagne

After two years of preparation, Piper launched WAHLKAMPAGNE: Eine Kunstaktion zur Bildungspolitik on schedule on January 1st, 2021, to coincide with national elections in Germany. This mixed-media work takes on the overcrowded and understaffed German educational system, which at a much earlier historical moment was the best in the world and provided the role model and structural foundation for every other high-functioning educational system in the world. The “≤15:1” formula at the bottom of the sandwich boards and lapel pins, which are distributed free of charge by the APRA Foundation Berlin, invites German citizens and residents to demand a student-teacher ratio of no more than 15 to 1 per class maximum, a basic condition for the successful transmission of knowledge in any field without which no other reforms are meaningful. Wahlkampagne also invites owners of buildings in Berlin to allow the Foundation to mount the three signs, in some configuration, on the facades of their buildings, also free of charge. In English translation, the signs say, “WITHOUT EDUCATION ➔ NO CHANCE ➔ NO CHOICE”. The German word Wahl means both “choice” and “vote,” so Wahlkampagne targets Germany’s political class, virtually all of whose members were up for (re-)election in 2021. The aim of the work is to encourage all German citizens and residents to surround German politicians with reminders – around the Bundestag, on all of the buildings, and on everyone’s lapels – that a first-class education for everyone, not only the elite, is a necessary precondition for solving any of the other pressing problems, of poverty, immigration, COVID-19, climate change, political extremism, etc., to which they regularly give priority. On 27 October 2021, the day following the induction of the newly elected members of the German Parliament, Piper declared her intention to donate to the Bundestag an interior installation designed especially for the plenary assembly hall in which they convene. One week later, APRAʼs charitable status was revoked and, during the ensuing year, its application to renovate its intended permanent domicile was rejected. It is nevertheless written into the rules governing the APRA Foundation Berlin that Wahlkampagne will continue, past Piper’s death, until the ≤15:1 student-teacher ratio is achieved in every class at every level, in every specialization, in every school and university, in every state in Germany.

Yoga Practice

Piper began her study and practice of yoga in 1965 with the Upanishads and Swami Vishnudevananda’s Complete Book of Yoga. She studied with Swami Satchidananda from 1966, became a svanistha in 1971 and a brahmacharin in 1985. Between 1992 and 2000, she studied at Kripalu with Gitanand and with Arthur Kilmurray, Patricia Walden, Chuck Miller, Erich Schiffmann, Leslie Bogart, Richard Freeman, Tim Miller, David Swenson, Gary Kraftsow, Georg Feuerstein, David Frawley, and John Friend. Her asana practice, grounded in Iyengar principles, is vinyasa- and pranayama-based. Her meditation practice is samyama-based and follows the Samkhyan structure of the 24 Tattvas, but regards these as equivalent to the Five Koshas and the Vedantic Atman as the actual referent of the Samkhyan concept of Purusha.

The APRA Foundations

Adrian Piper founded the Adrian Piper Research Archive (APRA) in 2002, after being diagnosed with a chronic, progressive, and incurable medical condition. Although the condition had vanished within two years after she emigrated to Germany in 2005, she continued to develop APRA as a personal and public resource for students, scholars, curators, collectors, writers, and members of the general public who have a constructive curiosity or scholarly or professional interest in her work and life.[49]

APRA is maintained as a document of Piper's activities in her three chosen areas of specialization: art, philosophy and yoga. It comprises (1) the archive, housing Piper’s art work, correspondence, manuscripts, documents, family photo and letters archive; book, catalogue and articles library; video and soundwork library; reproductions library; Vedic and Western philosophy library; art book library, fiction and poetry library, music collection, video collection; artwork inventory, text inventory; and, eventually, preserved personal living and working space, furnishings, and personal possessions exactly as she designed, built and arranged and/or used them; and (2) the APRA web site, offering professional and biographical information about Piper’s life and work.[50]

In 2009 Piper established APRA as a foundation that also funded the APRA Foundation Berlin Multidisciplinary Fellowship, a single, annual competitive research grant designed for intellectuals who (i) are proven high achievers in at least two seemingly disparate fields of scholarship and/or the arts simultaneously; and (ii) wish to use APRA’s resources to research the conception, constitution and/or structure of the self in either or both of them.[51] In 2018 she added the APRA Foundation Berlin Philosophy Dissertation Fellowship, a single competitive research grant to a dissertation candidate who has completed a cross-cultural course of study in philosophy that includes two logic courses, Indian philosophy, Chinese philosophy, and the Arabic and Jewish thinkers in Medieval philosophy, in addition to the usual course requirements offered in most academic philosophy departments. The Fellowships aim to extend and encourage further investigation into the same broad family of concepts and theories that Piperʼs own research in philosophy and art engages. Their shared goal is to identify the constructive influence of cross-culturation and globalization on the development of divergent modes of creative self-expression; and to illuminate how these, in turn, can help one to adapt to and flourish in that panoply of divergent cultures.

In 2022 Piper established the Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation, a Scottish Charitable Incorporated Organization (SCIO #SC05 2211), to take over funding and administration of both fellowships, to establish and administer the permanent physical domicile of the Archive, and to organize multidisciplinary cultural and educational events on its premises. Henceforth the primary activities of the APRA Foundation Berlin will be to more fully develop the Wahlkampagne project within Germany, to distribute its print book publications, and to disseminate Adrian Piperʼs artwork through exhibition loans and screenings. In addition, the APRA Foundation Berlin has applied for permission to the German authorities to donate its assets to the Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation, in order to further the same charitable goals for which it itself was originally established: education and research that exemplifies, models, analyzes, and/or theorizes those creative multidisciplinary expressions of the self, encouraged by globalization and cross-cultural journeying, that Piper's own work also embodies.[52]

Fellowships and Awards

Adrian Piper has been a Non-Resident Fellow of the New York Institute for the Humanities at New York University since 1996. She was a Scholar at the Getty Research Institute in 1998-1999. She has been awarded Guggenheim, AVA, NEA, NEH, Andrew Mellon, Woodrow Wilson, IFK and Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin Institute for Advanced Study Research Fellowships, as well as the Skowhegan Medal for Sculptural Installation and the New York Dance & Performance Award (the Bessie) for Installation & New Media. In 2012 she received the College Art Association Artist Award for a Distinguished Body of Work, for having “since the late 1960s, … profoundly influenced the language and form of Conceptual art;”[53] and in 2014, a Women’s Caucus for Art Lifetime Achievement Award.[54] Piper’s mixed media installation in the 56th Venice Biennale 2015, The Probable Trust Registry (2014) won the Golden Lion Award for Best Artist.[55] In 2018, Piper was awarded the Käthe-Kollwitz-Preis from Germany’s Akademie der Künste, where she premiered her mixed media installation, Das Ding-an-sich bin ich (2018) at its prize exhibition. Piper is the first American to have received this honor, and was elected to membership in the Akademie der Künste the following year. In 2021, she was the winner of the Goslarer Kaiserring and was elected to membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She was the recipient of the Harvard Arts Medal in 2023.

References

By Adrian Piper:

- Selected Articles and Book Chapters in Philosophy:

- “Utility, Publicity, and Manipulation,” Ethics 88, 3 (April 1978), 189-206

- “Property and the Limits of the Self,” Political Theory 8, 1 (February 1980), 39-64

- “A Distinction Without a Difference,” Midwest Studies in Philosophy VII: Social and Political Philosophy (1982), 403-435

- “Two Conceptions of the Self,” Philosophical Studies 48, 2 (September l985), 173-197, reprinted in The Philosopher’s Annual VIII (1985), 222-246

- “Instrumentalism, Objectivity, and Moral Justification,” American Philosophical Quarterly 23, 4 (October 1986), 373-381

- “Moral Theory and Moral Alienation,” The Journal of Philosophy LXXXIV, 2 (February 1987), 102-118

- “Personal Continuity and Instrumental Rationality in Rawls’ Theory of Justice’,” Social Theory and Practice 13, 1 (Spring 1987), 49-76

- “Pseudorationality,” in Amelie O. Rorty and Brian McLaughlin, Eds. Perspectives on Self-Deception (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1988), 297-323

- “Hume on Rational Final Ends,” Philosophy Research Archives XIV (1988-89), 193-228

- “Higher-Order Discrimination,” in Amelie O. Rorty and Owen Flanagan, Eds. Identity, Character and Morality (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1990), 285-309; reprinted in condensed form in the monograph series Studies on Ethics in Society (Kalamazoo, Mich.: Western Michigan University, 1990)

- “’Seeing Things’,” Southern Journal of Philosophy XXIX, Supplementary Volume: Moral Epistemology (1990), 29-60

- “Impartiality, Compassion, and Modal Imagination,” Ethics 101, 4, Symposium on Impartiality and Ethical Theory (July 1991), 726-757

- “Xenophobia and Kantian Rationalism,” Philosophical Forum XXIV, 1-3 (Fall-Spring 1992-93), 188-232; reprinted in Robin May Schott, Ed. Feminist Interpretations of Immanuel Kant, (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997), 21-73; and in John P. Pittman, Ed. African-American Perspectives and Philosophical Traditions, (New York: Routledge, 1997)

- “Making Sense of Value,” Ethics 106, 2 (April 1996), 525-537

- “Kant on the Objectivity of the Moral Law,” in Andrews Reath, Christine M. Korsgaard and Barbara Herman, Eds. Reclaiming the History of Ethics: Essays for John Rawls, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997)

- “Kants intelligibler Standpunkt zum Handeln,” in Hans-Ulrich Baumgarten and Carsten Held, Eds. Systematische Ethik mit Kant, (München/Freiburg, 2001)

- “Intuition and Concrete Particularity in Kant’s Transcendental Aesthetic,” in F. Halsall, J. Jansen and T. O’Connor, Eds., Rediscovering Aesthetics (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2008)

- “Kantʼs Self-Legislation Procedure Reconsidered,” Kant Studies Online 2, 14 (20 October 2012): 203-277.

- “Reality Check. Where is Enlightenment? Adrian Piper responds.” Artforum 56, no. 10 (Summer 2018). https://www.artforum.com/print/201806/where-is-enlightenment-adrian-piper-responds-75518

- “The Logic of Kantʼs Categorical ʻImperativeʼ,” in Violetta L. Waibel, Margit Ruffing, and David Wagner, Herausg., Natur und Freiheit: Akten des XII. Internationalen Kant-Kongreßes (Boston/Berlin: Verlag de Gruyter, 2018): 2037-2045.

- “Philosophy En Route to Reality: A Bumpy Ride,” Journal of World Philosophies 4 (Winter 2019): 106-118.

- Books:

- Rationality and the Structure of the Self, Volume I. The Humean Conception (formally accepted for publication by Cambridge University Press [2008] and published as an open-access, online E-Book at http://adrianpiper.com/berlin/rss/index.shtml)

- Rationality and the Structure of the Self, Volume II. A Kantian Conception (formally accepted for publication by Cambridge University Press [2008] and published as an open-access, online E-Book at http://adrianpiper.com/berlin/rss/index.shtml)

- Escape to Berlin: A Travel Memoir. Berlin: The APRA Foundation Berlin, 2018. Distributed by the APRA Foundation Berlin https://www.adrianpiper.com/books/Escape_To_Berlin/index.shtml

About Adrian Piper:

- Selected Interviews and Critical Articles Primarily in Art:

- Allan, Hawa, “Fight or Flight: On Adrian Piper and the Escape to Freedom,” Epiphany: A Literary Journal, 9 July 2020. https://epiphanyzine.com/features/2020/7/9/fight-or-flight-on-adrian-piper-and-the-escape-to-freedom

- Altschuler, Bruce, “Adrian Piper: Ideas Into Art,” Art Journal 56, 4 (Winter 1997), 100-101

- Baldauf, Anette, “Rassismus und Fremdenangst: Gespräch mit der Konzeptkünstlerin und Philosophin Adrian Piper,” Wiener Zeitung Kulturmagazin, (Number 30, 1993), 16

- Bailey, David A., “Adrian Piper: Aspects of the Liberal Dilemma,” Frieze, October 1991, 14‑15

- Barrow, Claudia, “Adrian Piper: Space, Time, and Reference 1967-1970,” in Adrian Piper, (catalogue to accompany exhibition at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, England, September 1991), 11-15

- Bass, Chloë. “How Adrian Piper Challenges Us to Change the Ways We Live.” Hyperallergic, April 23, 2018. https://hyperallergic.com/439255/adrian-piper-museum-of-modern-art-retrospective/

- Berger, Maurice, Adrian Piper: A Retrospective (catalogue to accompany retrospective) (Baltimore: University of Maryland Baltimore County Press, 1999)

- Bowles, John P., “Adrian Piper and the Rejection of Autobiography,” American Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), Fall 2007

- Buskirk, Martha. “Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965–2016. Museum of Modern Art, New York.” Burlington Magazine 160, no. 1384 (July 2018): 597-599.

- Butler, Connie and Platzker, David, Eds. Adrian Piper: A Reader (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2018).

- Cherix, Christophe, Butler, Connie and Platzker, David, Eds. Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions 1965-2016 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2018).

- Cotter, Holland. “Adrian Piper: The Thinking Canvas.” New York Times, April 19, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/19/arts/design/adrian-piper-review-moma.html

- Dávila, Mela, Ed., Adrian Piper. Despe 1965, trans. Rodrigo, Cristina, Palou, Jordi, Perazzo, Martin (Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona, Barcelona, 2003)

- Del Principe, Robert, “Adrian Piper Interview: Rationality and the Structure of the Self,” APRA Foundation Berlin, May 2013, http://adrianpiper.com/philosophy-rss-video-interview.shtml

- Doran, Anne. “Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965-2016 @MoMA.” Collector Daily, June 15, 2018. https://collectordaily.com/adrian-piper-a-synthesis-of-intuitions-1965-2016-moma/.

- Farver, Jane, “Adrian Piper,” Adrian Piper: Reflections 1967‑87 (Retrospective Catalogue), (New York, N.Y.: The Alternative Museum, 1987)

- Fisher, Jean, “The Breath between Words,” in Maurice Berger, Adrian Piper: A Retrospective (catalogue to accompany retrospective) (Baltimore: University of Maryland Baltimore County Press, 1999), 34-44

- Franks, Pamela, “Conceptual Rigor and Political Efficacy, Or, The Making of Adrian Piper,” in Rhea Anastas and Michael Brenson, Eds. Witness to Her Art (Bard College, Center for Curatorial Studies, Annadale-on-Hudson: New York), November 2006, 75-82

- Gat, Orit. “The right to call herself anything she likes. Adrian Piper’s ceaseless exploration of identity.” The Times Literary Supplement, June 27, 2018. https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/private/the-right-to-call-herself-anything-she-likes/.

- Gau, Sønke, "Adrian Piper-Seit 1965: Metakunst und Kunstkritik," Camera Austria International, 79 (2002), 73-74

- Goldstein, Ann, “Adrian Piper,” Reconsidering the Object of Art: 1965-1975 (catalogue) (Los Angeles: The Museum of Contemporary Art, 1995), 196-199

- Gopnik, Blake. “Adrian Piper, Making Black Lives Matter Before ‘Black Lives Matter’.” June 4, 2018. http://blakegopnik.com/post/174573913705.

- Guarnaccia, Matteo, “Tele dal Gusto Acido alla Scoperta della Realtà,” in Alias (il Manifesto), Col 6, no. 14 (April 5, 2003), 4-5

- Hannaham, James. “Adrian Piper. Return of the Mythic Being: the Museum of Modern Art mounts a vast retrospective of the artist’s work.” 4columns, April 5, 2018. http://www.4columns.org/hannaham-james/adrian-piper

- Hayt‑Atkins, Elizabeth, “The Indexical Present: A Conversation with Adrian Piper,” Arts Magazine, (March 1991), 48‑51

- Heiser, Joerg, "Questionnaire: Adrian Piper," Frieze, no. 87 (November /December 2004), 126

- _________________, “The Great Escape: Adrian Piperʼs Memoir on Why She Went into Exile,” e-flux journal 103 (October 2019). https://www.e-flux.com/journal/103/291945/the-great-escape-adrian-piper-s-memoir-on-why-she-went-into-exile/

- Ives, Lucy. "Trust Survey 2018." Art in America, December 1, 2018. https://www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/magazines/trust-survey-2018/.

- Kester, Grant, “Adrian Piper in Concept,” The Nation 264, 4 (February 3, 1997), 25-27

- Little, Colony, “Unsynthesized Intuitions: Confronting Discomfort with Adrian Piper.” Culture Shock Art, December 12, 2018. https://cshockart.com/2018/12/12/unsynthesized-intuitions-and-confronting-discomfort-with-adrian-piper/.

- Maddex, Bobby, “Maximizing Clarity: An Interview with Conceptual Artist Adrian Piper,” Gadfly 1, 2 (April 1997), 22-25

- Mayer, Rosemary, “Performance and Experience,” Arts, (December 1972), 33‑36

- O’Neill-Butler, Lauren. “Adrian Piper Speaks! (for Herself).” New York Times (The Stone), July 5, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/05/opinion/adrian-piper-speaks-for-herself.html.

- _________________, “Adrian Piper in Conversation with Lauren OʼNeill-Butler,” November, No. 1 (17 July 2020) https://novembermag.com/contents/01

- Phelan, Peggy, “Portrait of the Artist, “ The Women’s Review of Books XV, 5, (February 1998)

- Phillpot, Clive, “Adrian Piper: Talking to Us,” Adrian Piper: Reflections 1967‑87, (Retrospective Catalogue), (New York: The Alternative Museum, 1987)

- Raven, Arlene, “Civil Disobedience,” The Village Voice, (September 25, 1990), Arts Section and Cover and 55, 94

- Rorimer, Anne, “New Art in the 60s and 70s: Redefining Reality,” (London: Thames and Hudson, 2001), 160-162, 164, 193

- Steinhauer, Jillian, “Outside the Comfort Zone. Adrian Piperʼs art plays with identity and confronts defensiveness.” The New Republic, May 30, 2018. http://adrianpiper.com/berlin/art/MoMA/docs/20180530JillianSteinhauerOutsideTheComfortZoneAdrianPiper%C2%B9sUncomfortableArt%20%20TheNewRepublic%20CorrAP.pdf

- Svenungsson, Jan, “An Artist’s Text Book,” (Helsinki: Finnish Academy of Fine Arts, 2007), 69-77

- Velasco, David. “Reveries of a Solitary Dancer. David Velasco on the art of Adrian Piper.” Artforum 57, no. 1 (September 2018). https://www.artforum.com/print/201807/david-velasco-on-the-art-of-adrian-piper-76329.

- Waleczek, Agata. “‘I Still Do Believe They Want Me Dead’: An Interview With Adrian Piper.” Frieze, September 10, 2018. https://frieze.com/article/i-still-do-believe-they-want-me-dead-interview-adrian-piper.

- Wilson, Judith, “’In Memory of the News and of Ourselves’: The Art of Adrian Piper,” Third Text 16/17, (Autumn/Winter 1991), 39‑62

- Yancy, George, “Adrian M. S. Piper, “ in George Yancy, Ed., African American Philosophers: Seventeen Conversations (New York: Routledge, 1998), 49-71

Footnotes

[1] Quoted from anonymous peer review reader’s reports for Volume I on pages 505-509 of Volume II; and from anonymous peer review reader’s reports for Volume II on pages 644-648 of Volume I.

[2] Adrian M. S. Piper, “Two Conceptions of the Self.” Philosophical Studies 48, 2. September l985 pages 173-197. Reprinted in The Philosopher’s Annual VIII, 1985, pp. 222-246.

[3] For the discussion of Hobbes, see Chapters I and XII. For the discussion of Hume, see Chapters XIII and XIV. For the discussions of Bentham, Mill and Sidgwick, see Chapter XII. For the discussion of virtue theory, see Chapters I and V, and also Chapter VI of Volume II. A Kantian Conception.

[4] See Chapters III and IV.

[5] See Rationality and the Structure of the Self, Chapter I. General Introduction to the Project: The Enterprise of Socratic Metaethics. This chapter is the introduction in both volumes.

[6] For discussion of the belief-desire model of motivation, see Chapter II. For discussion of the utility-maximizing model of rationality, see Chapters III and IV.

[7] See Chapter V.

[8] For the critique of Rawls, see Chapters VI.2 and X. For the critique of Thomas Nagel, see Chapter VII. For the critique of Brandt, see Chapter XI. For the critique of Gewirth, see Chapter IX.3. For the critique of Annette Baier, see Chapter XIII. For the critique of Williams, see Chapter VIII.3.2. For the critique of Frankfurt, see Chapter VIII.2. For the critique of Gibbard, see Chapter XII.5. For the critique of David Lewis, see Chapters II.1.3 and XII.5. For the critique of Alvin Goldman, see Chapter II.1.2. For the critique of Elizabeth Anderson, see Chapter IX.1. For the critique of Anscombe, see Chapter V.

[9] For analysis of the problem of moral motivation, see Chapter VI. For analysis of the problem of rational final ends, see Chapter VIII. For analysis of the problem of moral justification, see Chapter IX.

[10] See Chapter XV.

[11] Adrian M. S. Piper, “Kant on the Objectivity of the Moral Law.” In Andrews Reath, Christine M. Korsgaard and Barbara Herman, Eds. Reclaiming the History of Ethics: Essays for John Rawls. pp. 240-269. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

[12] Adrian M. S. Piper, “Kants intelligibler Standpunkt zum Handeln.” In Hans-Ulrich Baumgarten and Carsten Held, Eds. Systematische Ethik mit Kant, pp. 162-190. München/Freiburg, 2001. Available in English at http://adrianpiper.com/docs/intelstandpoint.pdf

[13] Rationality and the Structure of the Self, Chapter I.

[14] See Chapter II.

[15] See Chapter III.

[16] For the proposed solution to the problem of moral motivation, see Chapter V. For the proposed solution to the problem of rational final ends, see Chapter VIII.7. For the proposed solution to the problem of moral justification, see Chapters IX and X.

[17] For the idealized theory, see Chapters II and V. For discussion of its practical applications see Chapters VII and VIII.

[18] The problem of the whistle blower is analyzed in Volume I: The Humean Conception, Chapter VI.5.2. A solution to that problem is offered in Volume II. A Kantian Conception, Chapters VI.8 and IX.8.

[19] See Chapter XI.

[20] Adrian M. S. Piper, “Moral Theory and Moral Alienation.” The Journal of Philosophy LXXXIV, 2, pages 102-118. February 1987.

[21] See Chapter XI.8.

[22] http://www.adrianpiper.com/berlin/berlinjphil/editorial.shtml

[23] http://www.adrianpiper.com/berlin/berlinjphil/referees.shtml

[25] http://publicationethics.org/

[26] http://www.singaporestatement.org/

[27] Adrian Piper, “INFO: Plagiarism & Blind Submissions,” Philos-L E-List (http://listserv.liv.ac.uk/archives/philos-l.html), 7 April 2011.

[28] Adrian Piper, “INFO: Plagiarism & Blind Submissions.”

[29] http://www.adrianpiper.com/berlin/berlinjphil/editorial.shtml

[30] Adrian Piper, “Re: INFO: Plagiarism & Blind Submissions Digest,” Philos-L E-List (http://listserv.liv.ac.uk/archives/philos-l.html), 12 April 2011.

[31] http://www.adrianpiper.com/berlin/berlinjphil/referees.shtml

[32] http://adrianpiper.com/berlin/berlinjphil/anti_plagiarism.shtml

[33] http://www.adrianpiper.com/berlin/berlinjphil/docs/AnonRefContr.pdf

[34] Adrian Piper, “Re: INFO: Plagiarism & Blind Submissions Digest,” Philos-L E-List (http://listserv.liv.ac.uk/archives/philos-l.html), 12 April 2011.

[35] Breitwieser, Sabine, Ed. and Introduction Adrian Piper seit 1965: Metakunst und Kunstkritik, preface by Dietrich Karner. Vienna: Generali Foundation, 2002; Adrian Piper, „Self-portrait from the Inside Out, 1965“ and “LSD womb, 1965”, The War is over: 1945-2005 La libertá dell’arte. Exhibition catalogue, galleria d’arte moderna e contemporanea, p. 168. Bergamo, 2005; “Alice in Wonderland, 1966,” Metropolis M, Magazine on Contemporary Art, no.1, 2008. p. 75; Corgnati, Martina, “Adrian Piper sotto l'effetto dell' LSD, ” La Repubblica-Milano, online edition. December 7, 2002; Guarnaccia, Matteo, “18 pezzi psichedelelici, ” Il Manifesto, p. 15. December 19, 2002; Guarnaccia, Matteo, “Tele dal Gusto Acido alla Scoperta della Realtà,” in Alias (il Manifesto), pp. 4-5. Col 6, no. 14. April 5, 2003; Memeo, Francesca, “Gli anni Psichedelici di un artista contro il razzimo,” Vivere Milano, La Stampa, p. 10. November 21, 2002.

[36] Adrian Piper, “A Defense of the ‘Conceptual’ Process in Art, 1967,” in OUT OF ORDER, OUT OF SIGHT Volume II: Selected Writings in Art Criticism 1967-1992, pp. 3-4.Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1996; Adrian Piper, “My Art Education, 1968” in OUT OF ORDER, OUT OF SIGHT Volume I: Selected Writings in Meta-Art 1968-1992, pp. 3-7; Goldstein, Ann, “Adrian Piper,” Reconsidering the Object of Art: 1965-1975, pp. 196-199. Los Angeles: The Museum of Contemporary Art, 1995.

[37] Adrian Piper, “Xenophobia and the Indexical Present II: Lecture, 1992,” in Adrian Piper, OUT OF ORDER, OUT OF SIGHT Volume I: Selected Writings in Meta-Art 1968-1992, pp. 255-273.

[38] ibid. See also “Xenophobia and the Indexical Present I: Essay, 1988” pp. 245-251.

[39] Adrian Piper, “Hypothesis 1969 & 1992,” in Adrian Piper, OUT OF ORDER, OUT OF SIGHT Volume I: Selected Writings in Meta-Art 1968-1992, pp. 19-23.

[40] Adrian Piper, “Untitled Performance for Max’s Kansas City, 1970,” in Adrian Piper, OUT OF ORDER, OUT OF SIGHT Volume I: Selected Writings in Meta-Art 1968-1992, pp. 27-28; Adrian Piper, Talking to Myself, The Ongoing Autobiography of An Art Object. Bari, Italy. Marilena Bonomo, 1975; English-Italian, also Brussels, Belgium: Fernand Spillemaeckers, 1974; English-French. Reprinted in Adrian Piper, OUT OF ORDER, OUT OF SIGHT Volume I: Selected Writings in Meta-Art 1968-1992, pp. 29-55; Adrian Piper seit 1965: Metakunst und Kunstkritik, Ed. and Introduction by Sabine Breitwieser, Preface by Dietrich Karner. Vienna: Generali Foundation, 2002; Adrian Piper: Textes d’oeuvres et essais, Ed. Dirk Snauwaert. Villeurbanne: Institut d'art contemporain, 2003; Adrian Piper desde 1965, Ed. Mela Dávila, Introduction by Sabine Breitwieser. Barcelona: MACBA/ACTAR, 2003.

[41] Adrian Piper, “Art for the Artworld Surface Pattern, 1976” in Adrian Piper, OUT OF ORDER, OUT OF SIGHT Volume I: Selected Writings in Meta-Art 1968-1992, pp. 161-168. Also Adrian Piper: Reflections 1967-1987, Ed. Jane Farver. New York, N.Y.: The Alternative Museum, 1987; Adrian Piper, Ed. Elizabeth MacGregor. Birmingham, UK: Ikon Gallery and Cornerhouse, 1991; Adrian Piper: A Retrospective, Ed. Maurice Berger and Dara Meyers-Kingsley. Baltimore: University of Maryland Baltimore County Press, 1999.

[42] Adrian Piper, “Xenophobia and the Indexical Present I: Essay, 1988” in OUT OF ORDER, OUT OF SIGHT Volume I: Selected Writings in Meta-Art 1968-1992, pp. 245-251

[43] Adrian Piper: Reflections 1967-1987, Ed. Jane Farver. New York, N.Y.: The Alternative Museum, 1987; Brenson, Michael, “Adrian Piper,” The New York Times, p. C31. May 1, 1987; McEvilley, Thomas, “Adrian Piper,” Artforum XXVI, 1, pp. 128‑9. September 1987; Phillpot, Clive, “Adrian Piper: Talking to Us,” Adrian Piper: Reflections 1967‑87, Retrospective Catalogue. New York: The Alternative Museum, 1987; Smith, Virginia Warren, “The Art of Confrontation,” Atlanta Journal‑Constitution, pp. 12J‑13J. December 6, 1987; Hammond, Marsha, “Adrian Piper,” Art Papers 12, 2. pp. 40‑41. March/April 1988; Thompson, Mildred, “Interview: Adrian Piper,” Art Papers 12, 2, pp. 27‑30. March/April 1988; Raven, Arlene, “Colored,” The Village Voice, p. 92 . May 31, 1988; Lida, Marc, “Outside Looking In,” 108 Reviews 12, pp. 1, 5. May/June 1988; Art in America Editorial Board, “1987 in Review,” Art in America Annual 1988‑89 76, 8, p. 53. August 1988; Boyd, Wallace, “Image Reveals Personal Art,” The Emory Wheel, p. 8. Tuesday, October 18, 1988; Staniszewski, Mary Anne, “Conceptual Art,” Flash Art 143, p. 88. November/December 1988; Failing, Patricia, “Black Artists Today: A Case of Exclusion?,” Art News, pp. 124-131.March 1989; Sims, Lowery Stokes, “Mimicry, Xenophobia, Etiquette and Other Social Manifestations: Adrian Piper’s Observations from the Margins,” Adrian Piper: Reflections 1967‑1987. The John Weber Gallery, New York, NY, 1989; Marks, Laura U., “Adrian Piper: Reflections 1967‑87,” Fuse, pp. 40‑42. Fall 1990.

[44] Commissioned by the John Weber Gallery, New York and in the collection of the Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation Berlin, in Berlin, Germany.

[45] Commissioned by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York and in the collection of the Whitney Museum.

[46] What It’s Like, What It Is #1 was commissioned by the Washington Project for the Arts, Washington, D.C. and is in the collection Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum, N.Y. What It’s Like, What It Is #2 was commissioned by the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D. C. and is in the collection of the Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation Berlin, in Berlin, Germany. What It’s Like, What It Is #3 was commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art, N.Y. and is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art

[47] Black Box/White Box was commissioned by the Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio, and is in the collection of the Generali Foundation, Vienna.

[48] Vogel, Carol, “Inside Art: Philip Morris Loses an Artist,” The New York Times, November 24, 1995; Robinson, Walter, “Artworld: Tobacco Road, Part II,” Art in America 84, 1, p. 126. January 1996; Adrian Piper, “Philip Morris’ Artworld Fix,” The Drama Review 40, 4, pp. 5-6. Winter 1996; Adrian Piper, “Withdrawal Clarified,” Art in America 84, 4, p. 29. April 1996.

[49] http://www.adrianpiper.com/edinburgh/research.shtml

[50] http://www.adrianpiper.com/edinburgh/research.shtml

[51] http://www.adrianpiper.com/edinburgh/M-DFellowshipMenu.shtml

[52] http://www.adrianpiper.com/edinburgh/purpose_goals.shtml

[53] http://www.collegeart.org/awards/2012awards

[54] http://www.collegeart.org/news/2013/10/22/2014-lifetime-achievement-awards-from-the-womens-caucus-for-art/

See also

External links

- Adrian Piper Foundations

- Rationality and the Structure of the Self, Part I: The Humean Conception and Rationality and the Structure of the Self, Part II: A Kantian Conception

- Adrian Piper in the 56th Venice Biennale

- OUT OF ORDER, OUT OF SIGHT: Selected Writings in Meta-Art and Art Criticism 1967 – 1992 (MIT Press, 1996)

- Escape to Berlin: A Travel Memoir/ Flucht nach Berlin: Eine Reiseerinnerung

- Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions 1965-2016 [retrospective exhibition] The Museum of Modern Art, New York (27 March – 22 July 2018)

- Genealogical Information

- 1948 births

- Contemporary artists

- American artists

- 20th-century philosophers

- 21st-century philosophers

- Living people

- New Lincoln School alumni

- School of Visual Arts alumni

- City College of New York alumni

- Harvard University alumni